The Zookeeper’s Villa: Launch of the Jan & Antonina Zabinski Foundation

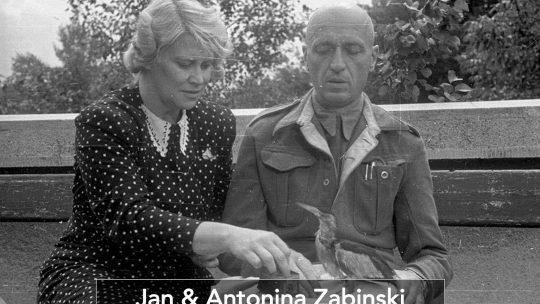

One of the most memorable and moving highlights of the 2019 edition of the CEEQA Gala was an interview on stage during the awards ceremony with some of the people connected to the story of Jan and Antonina Zabinski told in the movie “The Zookeeper’s Wife” starring Jessica Chastain, including the Zabinski’s daughter Teresa and grandson Dominik.

Many people have heard of Jan and Antonina Zabinski, or have seen the movie. But a great many more haven’t, and are completely unaware of the extraordinary tale of incredible personal heroism, bravery and human kindness that took place within the grounds of Warsaw Zoo during World War II, and their enormous legacy and lessons for wider humanity.

Many people have heard of Jan and Antonina Zabinski, or have seen the movie. But a great many more haven’t, and are completely unaware of the extraordinary tale of incredible personal heroism, bravery and human kindness that took place within the grounds of Warsaw Zoo during World War II, and their enormous legacy and lessons for wider humanity.

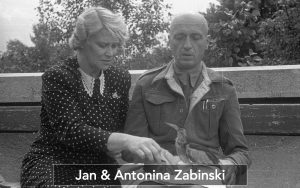

“Because it was the right thing to do”

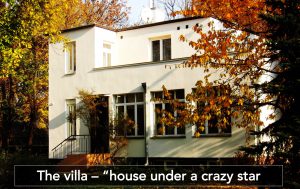

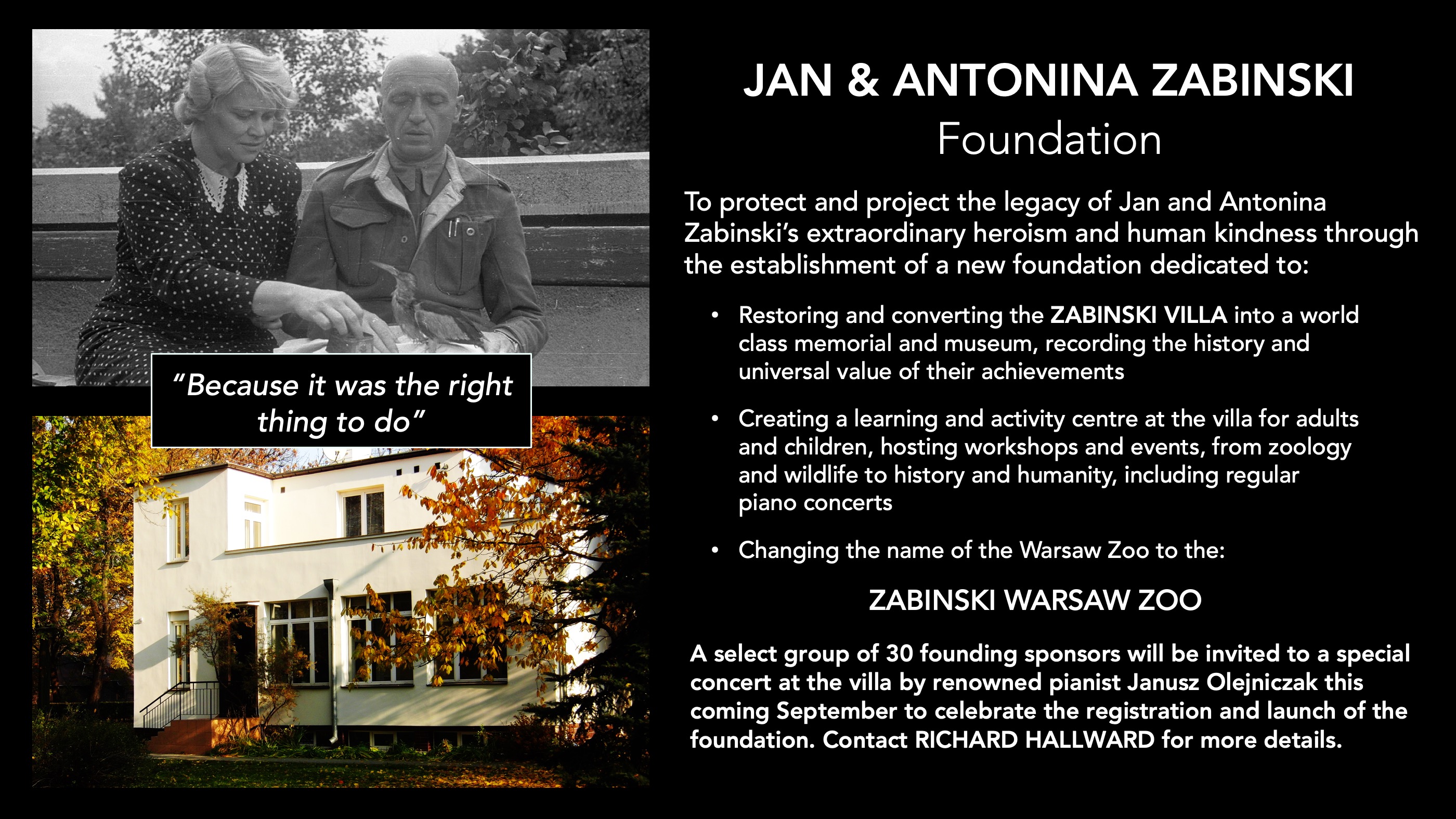

Or that the little zookeeper’s villa at the centre of the story, in the middle of the Warsaw Zoo, still stands today; a powerful but hidden and relatively neglected symbol of human unity and shared purpose, cared for over the years by small group of people associated with the zoo and with the Zabinski family, on something less than a shoe-string budget.

When asked why he and his family had placed themselves at such great personal risk to help so many strangers as well as people they knew, Jan Zabinski said simply that it was “the right thing to do.”

Also joining the interview with leading Polish broadcaster Monika Zamachowska in front of nearly 900 of the most prominent real estate investors in Central & Eastern Europe, at the sector’s annual “Oscars for business”, were the current President of the Panda Foundation engaged in the zoo’s maintenance, Ewa Rembiszewska, and her husband Maciej who directed the zoo for 28 years, as well as Janusz Oswiany, Professor of History at Warsaw Technical University who has played an important role in supporting restoration and historical archiving projects in the villa.

Also joining the interview with leading Polish broadcaster Monika Zamachowska in front of nearly 900 of the most prominent real estate investors in Central & Eastern Europe, at the sector’s annual “Oscars for business”, were the current President of the Panda Foundation engaged in the zoo’s maintenance, Ewa Rembiszewska, and her husband Maciej who directed the zoo for 28 years, as well as Janusz Oswiany, Professor of History at Warsaw Technical University who has played an important role in supporting restoration and historical archiving projects in the villa.

This small group of “zoo people”, together with members of the family, have informally performed the role of guardians of the villa over the decades and were responsible, largely from personal resources, for decorating the buildings interior with a few original artefacts to present to interested visitors to support the increased interest following the success of the movie, but without as yet an independent development budget or foundation status.

Protecting and projecting the Zabinski legacy

On the 80th anniversary of the beginning of that narrative, the organisers and partners of CEEQA are extremely proud and honoured to be able to present the “soft opening” of the Jan & Antonina Zabinski Foundation and to help lead its development.

On the 80th anniversary of the beginning of that narrative, the organisers and partners of CEEQA are extremely proud and honoured to be able to present the “soft opening” of the Jan & Antonina Zabinski Foundation and to help lead its development.

The mission of the new foundation is to protect and project the legacy and the lessons of the wartime deeds of the Zabinskis in Poland and internationally, focusing on the restoration of the villa and its establishment as a fittingly world class educational exhibit and monument to humanitarian duty, including building an extension to the villa for educational, profile building and fundraising activities.

Other goals of the foundation include a campaign to change the name of the zoo to the Zabinski Warsaw Zoo, and to support and partner with other organisations, nationally and globally, aimed at uniting humanity and honouring humanitarian deeds, including the eventual launch of an annual Jan & Antonina Zabinski award for humanitarian achievement.

Other goals of the foundation include a campaign to change the name of the zoo to the Zabinski Warsaw Zoo, and to support and partner with other organisations, nationally and globally, aimed at uniting humanity and honouring humanitarian deeds, including the eventual launch of an annual Jan & Antonina Zabinski award for humanitarian achievement.

What really happened at the Zoo

One or two Hollywood alternative facts aside, the movie is a largely accurate portrayal of how the Zabinskis coped with the challenges thrown at them during the war and Nazi occupation, using the zoo grounds and the villa itself to engage in clandestine activities to support the underground Home Army and managing to hide and help save more than 300 Jewish people “in plain sight” in the basement of the villa and in the zoo grounds, as well many others in great peril. Unlike in the movie, they were never found out.

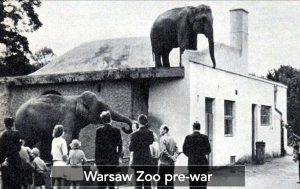

Co-founder of the Warsaw Zoological Gardens, and its director from 1929, Dr Jan Zabinski was highly regarded in zoological circles for developing the institution into one of Europe’s most celebrated and diverse zoological gardens, and lived an idyllic life with his wife Antonina and their young son Ryszard in the zookeeper’s villa, where their daughter Teresa was born during the war. The couple had met at the Warsaw University’s Institute of Zoology and Antonina shared Jan’s passion for animals, and was also a recognised author of children’s books.

Co-founder of the Warsaw Zoological Gardens, and its director from 1929, Dr Jan Zabinski was highly regarded in zoological circles for developing the institution into one of Europe’s most celebrated and diverse zoological gardens, and lived an idyllic life with his wife Antonina and their young son Ryszard in the zookeeper’s villa, where their daughter Teresa was born during the war. The couple had met at the Warsaw University’s Institute of Zoology and Antonina shared Jan’s passion for animals, and was also a recognised author of children’s books.

At the outbreak of the war in 1939 they were thrown into the role of protectors of the zoo’s history, knowledge bank and community, but in the ensuing bombardment of Warsaw they were forced to kill many of the animals, largely for public safety reasons, and eventually to turn the zoo into a pig farm to provide food rations for the occupying forces. Some of the most valuable animals were transported to zoos in the Reich for “safe-keeping”, including public favourite “Tuzinka”, only the 12th elephant to be born in captivity and the first in Poland.

Responsibility for the pig farm, and the subsequent allotment garden following the pig farm’s closure due to a dysentery epidemic, together with Jan’s appointment as Superintendent of the city’s public parks – as well as Jan’s less public role as a lieutenant in the underground Home Army – provided the Zabinskis with the access, networks and pretext to smuggle Jews out of the Warsaw Ghetto and provide them with refuge in the villa’s basement and in abandoned animal enclosures around the zoo. Some stayed for months, some for only a few days, as the Zabinskis helped to arrange counterfeit papers and safe houses for the fugitives to transit to. All crimes for which they and their whole family would have been summarily executed.

Responsibility for the pig farm, and the subsequent allotment garden following the pig farm’s closure due to a dysentery epidemic, together with Jan’s appointment as Superintendent of the city’s public parks – as well as Jan’s less public role as a lieutenant in the underground Home Army – provided the Zabinskis with the access, networks and pretext to smuggle Jews out of the Warsaw Ghetto and provide them with refuge in the villa’s basement and in abandoned animal enclosures around the zoo. Some stayed for months, some for only a few days, as the Zabinskis helped to arrange counterfeit papers and safe houses for the fugitives to transit to. All crimes for which they and their whole family would have been summarily executed.

An accomplished pianist, Antonina would play the piano in the drawing room of the villa: Offenbach to warn the fugitives of any danger, and Chopin when it was safe, among a series of coded messages to maintain the highly organised conspiracy. All the while fending off the curiosity of their housekeeper, who was a vehement anti-semite.

An accomplished pianist, Antonina would play the piano in the drawing room of the villa: Offenbach to warn the fugitives of any danger, and Chopin when it was safe, among a series of coded messages to maintain the highly organised conspiracy. All the while fending off the curiosity of their housekeeper, who was a vehement anti-semite.

All but two of the people they were able to help survived the war. And despite the occupying forces having a munitions store within the zoo grounds under constant surveillance, they also managed to conceal a weapons store for the underground Home Army there for eventual use in the Warsaw Uprising in which Zabinski himself participated, and was taken as a prisoner of war after being injured and captured.

Returning to Warsaw in 1945, Zabinski eventually resumed his duties and the couple set about rescuing what remained of the zoo’s assets and rebuilding it, officially re-opening the zoo in 1949 and continuing to live with their children Ryszard and Teresa in the little villa in the middle of the zoo grounds until 1951.

Recollection and recognition

While both Jan and Antonina have received high recognition and honours in many quarters over the decades, including recognition of Jan by the State of Israel as “Polish Righteous Among Nations” in 1965 and, more recently, the posthumous award of the “Commander’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta” to both of them by the Polish government in 2015, the full tale and message of their deeds was suppressed for decades under the previous communist regime along with many stories of Polish heroism.

In fact, after rebuilding the zoo following the war, Jan Zabinski was forced to resign his post as director in 1951 amid politically motivated accusations by the communist authorities of collaboration with the Nazis during the war.

In fact, after rebuilding the zoo following the war, Jan Zabinski was forced to resign his post as director in 1951 amid politically motivated accusations by the communist authorities of collaboration with the Nazis during the war.

The Zoo People

But among the many positive stories beneath that narrative is the story of a young boy that Jan Zabinski found strolling around the zoo grounds one day during school hours and, when asked why he wasn’t at school, the boy responded that the only thing that interested him was animals and that he planned to run the zoo one day. The boy, Maciej Rembiszewski, was eventually appointed director of the Zoo in 1981 and until 2009 presided over extensive modernisation of the zoos assets, facilities and social engagement, including establishment of the Panda Foundation to support and promote the zoo’s activities.

Maciej’s wife, Ewa Rembiszewska, is responsible today for the upkeep of the little villa at the heart of the zoo, known as the Zabinski Villa. Also an important figure in the story is Janusz Owsiany, professor of history at the Warsaw Technical University. The Zabinski’s daughter, Teresa Zawadzka-Zabinski remains closely connected with the villa and its work, as does her son and the Zabinski’s grandson, Dominik Zawadzki. Unfortunately the Zabinski’s son Ryszard, whose childhood was spent at the villa and is remembered fondly by survivors for smuggling food to them around the zoo grounds, passed away only a few weeks ago.

Maciej’s wife, Ewa Rembiszewska, is responsible today for the upkeep of the little villa at the heart of the zoo, known as the Zabinski Villa. Also an important figure in the story is Janusz Owsiany, professor of history at the Warsaw Technical University. The Zabinski’s daughter, Teresa Zawadzka-Zabinski remains closely connected with the villa and its work, as does her son and the Zabinski’s grandson, Dominik Zawadzki. Unfortunately the Zabinski’s son Ryszard, whose childhood was spent at the villa and is remembered fondly by survivors for smuggling food to them around the zoo grounds, passed away only a few weeks ago.

And while there has been a surge of interest in the villa and the story of the Zabinskis since the Hollywood movie released in 2017, the villa has never had its own financial or management platform to truly harness this interest and its universally resonant message, or the history that it has seen.

Next steps

The first step in the development of new foundation will be the recruitment of a group of “founding sponsors” to help finance, advise and support the first phase of its development objectives. The registration of the foundation is already in progress.

The first step in the development of new foundation will be the recruitment of a group of “founding sponsors” to help finance, advise and support the first phase of its development objectives. The registration of the foundation is already in progress.

Recalling the piano playing of Antonina Zabinska to send coded messages to the fugitives they harboured, this coming September we plan to invite a small group of 30 interested parties to attend a special concert in the drawing room of the villa to get the ball rolling, the invited pianist will be Janusz Olejniczak .

At next year’s CEEQA Gala we plan the formal launch of the Jan & Antonina Zabinski Foundation. and the unveiling of the first phase of the development project and campaign. Interested companies or people are invited to contact Richard Hallward, the director of CEEQA.